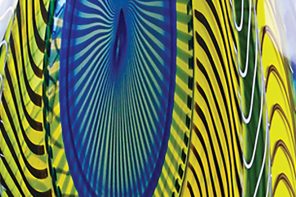

David Webb’s jewelry is synonymous with strikingly bold colors and large scale — and remains astonishingly popular today, nearly 50 years after the designer’s early death in 1975. The tens of thousands of sketches that David Webb left behind not only document his evolving style — but provide his eponymous firm with a treasure trove of designs that has kept it in business to this day. Webb was one of America’s premier postwar jewelers and his designs were largely tailored to a young and stylish clientele with a growing taste for a more casual style in women’s fashion. Webb’s subject matter varied widely — the bounty of the garden, African art, royal orders, astrology, Chinese works of art and pre-Columbian artifacts, as did his choice of stones. Among his favorites were coral, turquoise, jade and rock crystal. But his look was always fresh and visually strong, and this has ensured that Webb’s jewelry remains highly prized in both primary and auction markets today.

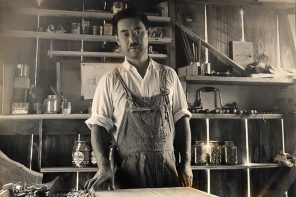

Asheville, North Carolina-born Webb (1925-1975) was nothing if not precocious — settling on a career as a jeweler before he hit double digits. He moved to New York City at 17, opened his first shop at age 23 and had his first Vogue cover by 25. By age 30, Webb’s work graced four Vogue covers in one year alone, and he jettisoned his wholesale business to commit wholeheartedly to a retail operation.

While natural talent and the unwavering admiration of fashion critics and publicists helped to garner jewelry placements (Revlon, Elizabeth Arden and movies such as “Pillow Talk” to name just a few), he was also aided by the patronage of style setters like Jacqueline Kennedy and the Duchess of Windsor. One of his biggest breaks was Jacqueline Kennedy’s 1962 commission to design the Gifts of State for the Kennedy administration.

Webb is most widely celebrated for his animal bracelets, which began steady production in 1963 and remain the best-selling pieces of the company. Webb was certainly not the first to embrace the idea of the animal bracelet. The chimera bracelet had been designed by Cartier in the 1920s, and was, in turn, inspired by Indian arm bracelets. But Webb took the idea and ran with it. There is endless variation in the Webb animals. Among the most popular are the African big cats, double frogs and the zebra, which also served as Webb’s company logo.

Another of Webb’s iconic designs was the Maltese cross. Verdura created the Maltese cross cuff for Coco Chanel in 1930, but Webb embraced the motif for bracelets, brooches and necklaces, which show the myriad choices of brightly colored enamels and colored stones, both hallmarks of Webb’s style.

Color was of paramount importance to Webb — evident in his use of colored enamels and colored stones. Webb favored colored precious and semiprecious stones over diamonds, elevating their importance and incorporating them into jewelry suited to both casual and evening dress. Traditionally, diamonds and platinum had been reserved for important jewelry. But in 1963 Webb said: “No longer does a woman think that her important pieces of jewelry need be diamonds. …The look today is color, flattered by diamonds in platinum or gold or mixed with other stones.”

Webb also incorporated out-of-fashion materials, like jade and rock crystal, into his designs. An inveterate museumgoer and antiques hunter, Webb scoured New York antiques shops for jade to set into his jewelry. Rock crystal, the favorite of the Art Deco period, was resurrected by Webb, who said it “is the one white alternative for diamonds.” Its lesser cost made it particularly appealing during the recessionary 1970s, while the noncolor of rock crystal was a distinctive advantage in casual dressing.

Yellow gold was always Webb’s preferred choice, often patinated to look old, or roughly textured to give a more casual look. The look was heavy and bold and drew inspiration from ancient civilizations. The precious metal was put to great effect in Webb’s line of zodiac-inspired jewelry. His brooches, bracelets and belt buckles capitalized on the interest in astrology in the 1970s and are highly sought after today.

You are left to wonder what else would have inspired Webb had his life not been cut so short at age 50 of pancreatic cancer. For while he would sketch infinite variations on a theme, he never tired of seeking out new inspiration.

For more, read Ruth Peltason’s “David Webb: The Quintessential American Jeweler.” Contact Jenny at jenny@ragoarts.com or 917-745-2730.