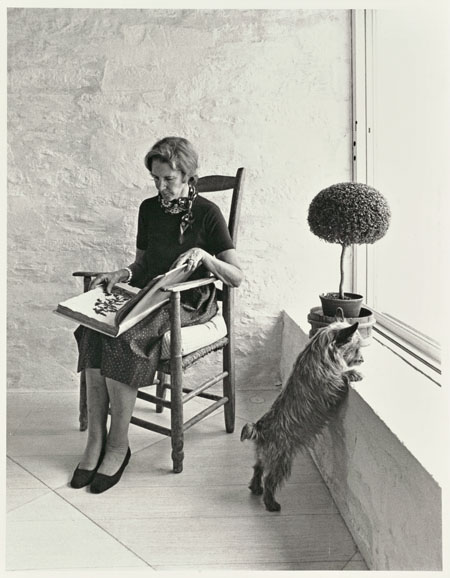

The legacy of Rachel Lambert “Bunny” Mellon continues to grow.

An American philanthropist best remembered as a significant garden designer and art collector, Mellon assembled an array of botanical artwork along with a library of more than 10,000 volumes on botanical subjects.

The collection, housed in the Oak Spring Garden Library that Mellon (1910-2014) founded on her estate in Upperville, Va., not only fueled her professional work but also served to reflect her personal interests in Oak Spring’s greenhouses and gardens.

And now, nearly 80 works from the collection — ranging from the 14th through 20th centuries with many never before exhibited publicly — will be spotlighted in “Redouté to Warhol: Bunny Mellon’s Botanical Art.”

The showcase, a virtual primer on botanical works of art, opens Oct. 8 at the New York Botanical Garden. It will continue through Feb. 12, 2017 in the Art Gallery of the LuEsther T. Mertz Library on the garden’s Bronx grounds.

It is co-curated by Lucia Tongiorgi Tomasi, an expert on herbals and botanical art and author of two publications documenting the Oak Spring Garden Library collection; Susan Fraser, vice president and director of the LuEsther T. Mertz Library at the NYBG; and Tony Willis, librarian of the Oak Spring Garden Library.

Showcasing Mellon was far from a random choice, says Fraser.

“Mrs. Mellon was on the New York Botanical Garden’s board in 1967. She was associated with the Garden for quite a while.”

And, she adds, the NYBG has an ongoing relationship with both the Oak Spring Garden Library and the Oak Spring Garden Foundation that maintains the library and promotes scholarship and public education in the fields of botany, horticulture and landscape design.

The curators, Fraser says, were all more than familiar with the library’s holdings through their work.

“She has an amazing collection. It rivals any private library in the world.”

And visitors to the NYBG should expect to be not only dazzled but also surprised.

After all, Mellon, whose notable efforts included designing the White House Rose Garden during the John F. Kennedy administration, both collected — and displayed her collection — in a distinctive fashion that the exhibition will strive to echo.

“We’re really trying to evoke Mrs. Mellon’s style,” Fraser says. “She had this sort of singular vision.”

And that vision, Fraser adds, extended to her library and her gardens.

“It’s unbelievable,” she says. “I was there four times now. It’s like a little piece of heaven on earth. I don’t even know how to say it. It’s just idyllic.”

There was, it seems, an adventurous and daring spirit at work.

“On the walls she had Dutch still lifes next to giant Mark Rothkos,” Fraser adds.

The curators, Fraser says, were invited to shape the NYBG show themselves and so drew inspiration from Mellon’s individual approach.

“We really had carte blanche.”

That meant discovering and choosing from often-rare masterpieces from noted botanical artists such as 16th-century master Jacques Le Moyne de Morgues and Pierre-Joseph Redouté (1759–1840) to more modern artists, including Pablo Picasso and Andy Warhol.

What will surprise people the most?

“I think probably the breadth of her collection,” Fraser says, with Mellon’s interests reflected in her gathering.

“She collected a lot of botanical works from the French courts,” she adds, and was also fascinated with the 17th-century craze for tulips — and tulip-themed art — in Holland.

This exhibit is very large in scale for the library, with rare illustrated manuscripts, works on paper, paintings and three-dimensional objects creating what Fraser described as a “dense” examination.

“We had a hard time taking things away,” Fraser says.

In fact, there was one instance in which that just wasn’t possible.

“She has 17 of the most remarkable works by Jan van Kessel. They’re phenomenal. They’re just phenomenal,” Fraser says.

These works by the Dutch artist (1626-79) will be displayed in a manner that pays homage to a cabinet of curiosities.

Fraser says that Mellon was part of a small group of devoted collectors, also mentioning women such as Mildred Barnes Bliss and Rachel Hunt, whose efforts secured them a place in botanical history.

“I think it’s sort of an era gone by, where people were able to collect and have libraries like that,” Fraser says.

And in recognizing the work of a collector such as Mellon, the exhibition seems to encourage contemporary eyes to look at botanical works in a new light — something Mellon was doing all along.

As Fraser says, “This sort of breaks boundaries in a sense.”

For more on the exhibition, visit nybg.org. For more on Mellon, visit oakspring.org.

![Cristofaro Munari, attrib. (Italian, 1667– 1720) A quince, an apple, two lemons, and three blue and white cups], ca. 1700 Oil on canvas. Courtesy Oak Spring Garden Library.](https://www.wagmag.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Munari-still-life.jpg)

![Georg Dionysius Ehret (German, 1708–70) [Magnolia grandiflora (Southern Magnolia)], ca. 1737 Bodycolor on vellum. Courtesy Oak Spring Garden Library.](https://www.wagmag.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Ehret-Magnolia-grandiflora-.jpg)