I have been in love with the ancient Greeks since I was a child. It began with a Scholastic book on the Greek gods and my beloved Aunt Mary, who raised me. A Kennedy Democrat, she filled our home — and my head — with the writers Jackie loved and turned to, particularly in times of tragedy.

The dramatists Aeschylus, Euripides and Sophocles. The poets Homer, Pindar and Sappho. The philosophers Aristotle, Plato and Socrates. The historians Herodotus and Thucydides. I read them all, perhaps when I should’ve been enjoying family and friends. But I couldn’t get enough, especially of those mercurial gods — stars in a high-class soap opera that offered me, a convent schoolgirl, glamour and sex under the guise of a traditional, classical, nun-approved education. It was only later when faced with adult heartaches that I realized how much the ancients have taught me about living life — and accepting loss — with honor.

By the time I discovered Alexander the Great, the Greco-Macedonian king whose conquest of the Persian Empire in 331 B.C. would lead to the dissemination of post-classical Greek culture (Hellenism) and whose birthday I shared, I had found a kindred spirit — one who showed me how to cope with difficult parents and manage people.

“You should ask yourself why you’re so in love with someone who’s been dead for more than 2,000 years,” cautioned my aunt, who was born on the anniversary of Alexander’s conquest of Persia (Oct. 1).

I didn’t have to. The Greeks fired my imagination, and I returned that fire with faithfulness, even as I despaired over the decline in interest in them — spurred in America by the devaluing of traditional classical education and the failure of Alexandrian leadership (leadership from the front). Indeed, a recent New York Times article suggested that the reason The Museum of Modern Art is thriving financially while The Metropolitan Museum of Art struggles is because we’re no longer interested in the past. Modernism and contemporary art are where it’s at in the digital age.

But we live with the past, not in it. It informs the present and the future. And so it was with great joy that I’ve detected a Greek revival, if you will, in a spate of exhibits and books that have taken me on my own odyssey.

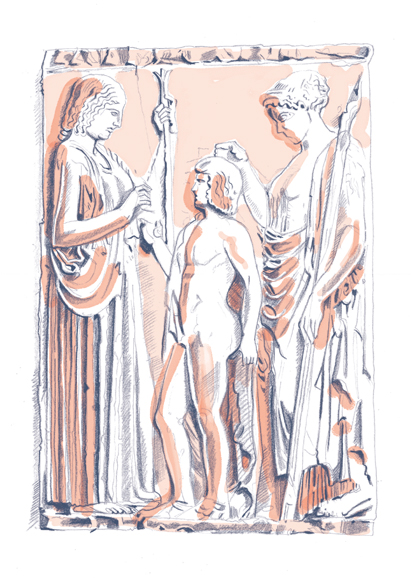

It began last year with an article in the magazine Minerva — named for the Roman version of Athena, the Greek goddess of wisdom, with whom I identify intensely —announcing two major exhibits, the Portland Art Museum and The British Museum’s “The Body Beautiful in Ancient Greece,” which celebrated the Greek perfection of the human form, and “Power and Pathos: Bronze Sculpture of the Hellenistic World.” Alas, I couldn’t get to Portland or London, and a search for “The Body Beautiful” catalog on Amazon — named for the female warriors whose power impressed even Alexander and his legendary ancestor, Achilles — yielded nothing.

Patience, I thought, your moment will come. And it did as I went to Washington, D.C. at Christmastime to see my family and “Power and Pathos” at the National Gallery of Art. I had warned the family that the National Gallery show was all I wanted for Christmas. They received the news with a resigned equanimity worthy of the Stoics (Roman philosophers but still, close enough to the Greeks). The youngest of the clan, teenaged James, was drafted to accompany me, and he and I soon found ourselves standing before “Alexander the Great on Horseback,” a Roman copy of the Greek original. I had known this work, housed in Naples, all my life only from books. Now here I was face-to-face with it. “I’m so happy I could cry,” I told James, who took this in manly stride. As we wandered through the show and catalog — which charted the increasing realism in the Hellenistic portrayal of the human figure — I suggested we play a game. “Let’s try to find Greek influences throughout the museum.”

And we did — in works of the Renaissance, of course, neoclassical (turn-of-the-19th-century) Paris and Art Deco (1920s) America — the last represented by Paul Manship’s angular “Diana and a Hound,” Diana being the Roman Artemis, goddess of the hunt.

After that and having secured at last a copy of “The Body Beautiful” in the exhibit gift shop, James and I rested from our Herculean labors at the all-you-could-eat Greek buffet in the museum’s Garden Café.

As winter gave way to spring, my Greek odyssey intensified. Unable to get to The Field Museum in Chicago for “The Greeks — Agamemnon to Alexander the Great” — I’ll try to catch up with it at the National Geographic Museum in Washington, D.C. (through Oct. 9) — I couldn’t wait to treat myself to the small accompanying catalog and a stamp-sized paperweight that reproduced a handsome coin of Alexander with the ram’s horns of the sky god Zeus Ammon entwined in his luxuriant locks. I devoured Thames & Hudson’s “Greek Mythology: A Traveller’s Guide From Mount Olympus to Troy,” “Mythology: An Illustrated Journey Into Our Imagined Worlds” and “Persian Painting: The Arts of the Book and Portraiture,” which offers plenty of sensuous illuminated manuscript folios of Alexander’s adventures from the Persian perspective.

On Good Friday, I took in “Gods and Mortals at Olympus: Ancient Dion, City of Zeus” (through June 18 at the immaculately revamped Onassis Cultural Center NY in Manhattan) before heading across the street for services at St. Patrick’s Cathedral.

But the mother lode was still to come — “Pergamon and the Hellenistic Kingdoms of the Ancient World” (through July 17 at The Met). Here was the fulfillment of 35 years of covering the arts and a lifetime of loving the ancients at the intersection of gorgeous objects and intellectual inquiry.

In the first gallery, I encountered the “Alexander on Horseback” I had seen in Washington amid various Alexanders.

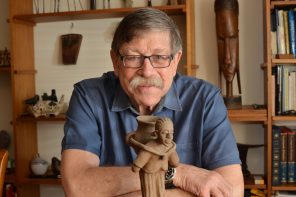

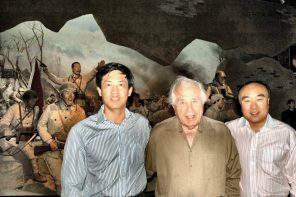

“Enough Alexanders for you?” a Met spokeswoman teased, knowing my fondness. “There can never be enough,” I replied. When I interviewed exhibit co-organizer Seán Hemingway during a second visit, this time with WAG photographer John Rizzo, I realized he knew what I meant. Hemingway autographed his debut novel, “The Tomb of Alexander,” for me with an inscription that any Alexandrian knows is the password sailors must give to mermaids to ensure a safe voyage in the wine-dark Mediterranean. Perhaps I was a mermaid in a previous life.

“Alexander lives and reigns,” Hemingway inscribed my copy.

For me, he and the Greeks always will.