One was sleekly sexy; the other, charmingly chubby. One was aloof and arrogant; the other, a people person. And yet, both were larger than life figures who crystallized their art forms for global audiences, becoming the standards by which those arts are measured. Indeed, even today, you’ll hear someone say, “He’s a real Nureyev” or “He’s a real Pavarotti.”

More likely, you’ll hear someone say, “Well, he’s no Nureyev” or “Who does he think he is? Pavarotti?” They were sui generis, and now they’ve both been captured on the big screen.

The documentary “Pavarotti: Genius is Forever,” by

Oscar-winning director (and former Greenwich resident) Ron Howard — in theaters June 7 — considers the solitary complexity behind the gregarious performer who gave himself to music, international audiences and humanitarian causes, often at the expense of family life.

It follows on the heels of Ralph Fiennes’ thriller-style feature “The White Crow,” which charts the taut, fraught days leading up to the incandescent but rebellious Nureyev’s leap from behind the Iron Curtain in 1961 while the dancer was performing with the Kirov Ballet in Paris. A week before the April release of “The White Crow,” the documentary “Nureyev,” offering a fuller picture of the dancer’s equally complex life, debuted.

Before they were legends, however, both men had to overcome many challenges to make that leap to fame. Their earliest was poverty. Many are familiar with the story of Nureyev’s birth on March 17, 1938 aboard a Trans-Siberian train bound for Vladivostok where his father instructed soldiers. That event was subsequently mythologized to foreshadow the perpetual motion and greatness he ultimately achieved. But Nureyev and his family, of Tartar Muslim descent, lived in cramped quarters, first in Moscow for part of World War II and then in Ufa, where Nureyev, a loner, found his calling in dance.

The arts were also an early influence — along with soccer — on the life of Pavarotti, who grew up in equally straightened circumstances outside Modena, Italy, where he was born Oct. 12, 1935 to a cigar factory worker and a baker who was a talented tenor too nervous for the stage. Abandoning his dream of becoming a soccer goalie,

Pavarotti listened to his father’s recordings of singers like Mario Lanza and sang with him in the church choir, beginning to study voice seriously at age 19.

Singers, who generally must wait until at least the teenage years for the voice to mature, tend to develop later than dancers, who start training between the ages of 4 and 8. Nureyev’s early success in folk dancing and with the Ufa Opera Ballet led teachers to encourage him to study at the Vaganova Academy of Russian Ballet in what is now St. Petersburg. There at age 17 he worked with legendary teacher Alexander Pushkin (played by Ralph Fiennes in “The White Crow”), who would later train Mikhail Baryshnikov.

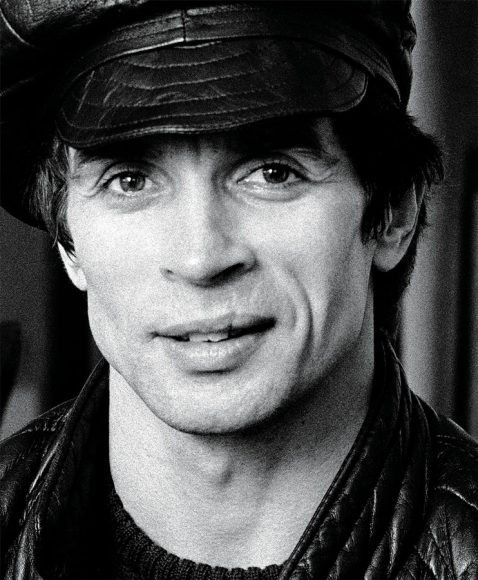

Graduating in 1958, Nureyev joined the Kirov (today the Mariinsky Ballet), where his visceral charisma, leonine stage presence and lofty carriage — accentuated by rising high on the ball of the foot — more than compensated for what some saw as a less than perfect technique. But the self-possessed, headstrong Nureyev played a dangerous game in defying both Kirov and Soviet authorities.

If Nureyev was defiant in the late ’50s, Pavarotti was doubtful. His career consisted of a series of unpaid gigs that had him earning a living as an elementary schoolteacher and insurance salesman. Then a

vocal chord nodule and a disastrous performance in Ferrara led him to give up singing. The moment he let go, however, was the moment Pavarotti — always a nervous Nelly before going onstage — relaxed. The nodule disappeared. And he found his natural voice — as bright, clear and penetrating as a bell.

The spring of 1961 would be pivotal for both. In April, Pavarotti made his debut in what would become a signature role, as the lovestruck, struggling poet Rodolfo in Giacomo Puccini’s “La Bohème,” at the Teatro Municipale in Reggio Emilia. Two months later, after playing a tense cat-and-mouse game with his Kirov and KGB handlers in Paris, Nureyev defected. It was not a physical leap, of course, but rather a metaphoric one to self-determination as returning to Russia might’ve meant the end of his career and even imprisonment. A sensation in Paris, Nureyev was now a cause célèbre worldwide, forming a memorable partnership with the Royal Ballet’s prima

ballerina, Margot Fonteyn, onstage and the Danish danseur Erik Bruhn off. In each case, Nureyev brought a Dionysian fervor to their Apollonian elegance.

Pavarotti’s breakthrough partnership would follow when he was asked to team with Australian coloratura soprano Joan Sutherland for a tour of her native land. Possessed of both a mischievous sense of humor and a love for the ladies, the twice-married Pavarotti would later say he learned the immaculate breathing technique that would sustain him in good days and bad by embracing her diaphragm during some of opera’s most romantic scenes. Subsequent performances as the ardent Tonio in Gaetano Donizetti’s “La Fille du Régiment” — in which he tossed off high Cs to record-breaking curtain calls at The Metropolitan Opera — would lead him to be dubbed “the king of the high Cs.”

“He would open his mouth,” friendly rival tenor Placido Domingo says in “Pavarotti,” “and everything was easy.”

Or maybe the great ones make it seem easy. What made Pavarotti and Nureyev great rather than good was in part their ability to take the road wherever it led. They did not shrink from risks, even when the results were less than stellar — Nureyev in the 1977 film “Valentino” and Pavarotti in the 1982 movie “Yes, Giorgio.” They knew what it was like to feel the critics and audience’s wrath. Pavarotti was booed when his voice cracked in a 1983 performance of Donizetti’s “Lucia di Lammermoor” at La Scala, scene of some of his greatest triumphs. Nureyev earned mixed reviews for his 1979 Broadway tribute to early 20th- century dancer Vaslav Nijinsky, although I will never forget his performance there as the abused puppet in Mikhail Fokine’s “Petrushka,” so full of pathos, or the half-hour ovation that rained down on him at the March 17 performance, which also marked his birthday.

Still, they continued to push the boundaries of their art. Nureyev danced for Martha Graham and Paul Taylor, directed and choreographed for the Paris Opera Ballet (1982-89) and played the Palace Theater in Stamford as the King of Siam in Rodgers and Hammerstein’s “The King and I” in 1991 after a Broadway run. Pavarotti sang with Bono and on NBC’s “Saturday Night Live,” the only opera singer to do so. In 1990, he teamed with Domingo and fellow tenor José Carreras to celebrate the World Cup and Carreras’ return from his successful battle with leukemia, spawning a host of imitators as The Three Tenors.

In the end, they were wildly different men. Pavarotti had a teddy bear persona exemplified by his work with the Red Cross and refugees. Though he had an egotistical reputation, Nureyev was in conversation engaging and surprisingly self-deprecating, with an autodidact’s hunger for knowledge and a sophisticate’s refined, wide-ranging taste.

Nureyev died of AIDS complications in Paris — the city that introduced him to the West — on Jan. 6, 1993. Pavarotti died of pancreatic cancer at his home in Modena on Sept. 6, 2007. What they shared was their ability to move us with their art.

As new attempts to understand them demonstrate, they move us still.