Recently, I had the pleasure of writing an essay for a new monograph on the contemporary Colombian artist Federico Uribe — whose haunting mixed-media paintings and sculptures draw on a difficult childhood, his complex relationship with Roman Catholicism and the violence of his homeland to explore issues of sex/gender, passion and the body, among others.

“Federico Uribe: Watch the Parade” (Skira, April 24, 208 pages, $50) is truly a local labor of love. It originated with Manhattan’s Adelson Galleries, owned by Warren and Jan Adelson, who lived in Westchester County for many years. (Jan is the former chair of the Hudson River Museum in Yonkers, where Uribe made a sensational showing in “Fantasy River,” a 2013 exhibit of his work.)

The book is edited by Bartholomew F. Bland, executive director of the Lehman College Art Gallery in The Bronx and former deputy director of the Hudson River Museum. (He continues his relationship with the museum this month as guest curator of “The Neo-Victorians: Contemporary Artists Revive Gilded-Age Glamour.”)

“Watch the Parade” also gives Uribe fans and newcomers alike an opportunity to explore the breadth of his interests, including a love of nature and a willingness to consider its shadow side.

My essay plumbs but one facet of an artist whose work is often located where many of us live — at the intersection of fear and desire.

My thanks to the Adelson Galleries and Bland for the opportunity to participate in this fascinating project and for permission to reproduce the essay:

It’s not just the title of a Felice and Boudleaux Bryant song made famous by the Everly Brothers. It crystallizes Federico Uribe’s exploration of the body, sex and romance in his art.

“Initially, his formation began as a painter with sensual and brooding canvases influenced by his dark reflections on the (Roman) Catholic sense of pain, guilt and sexuality,” his website declares. And Uribe himself has hinted at Dickensian forces down on the farm of his Colombian youth. “I had a terrible childhood for many reasons,” he told The New York Times on the occasion of his 2013 exhibition “Fantasy River,” at the Hudson River Museum in Yonkers, New York.

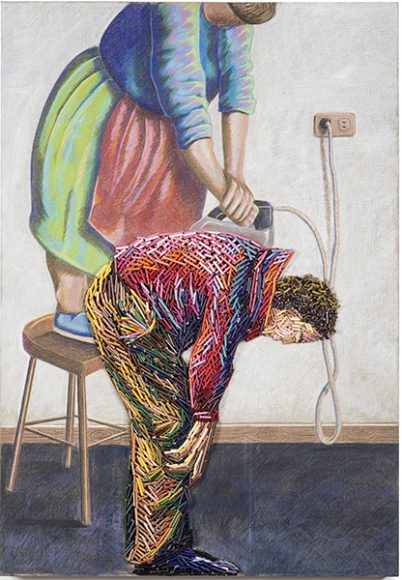

How terrible is suggested in the painting “Obedience” (2014), in which a Fernando Botero-stout woman stands on a chair and irons the back of a boy — a bent figure made of shards of color, like Uribe’s sculptures of found objects. Try as she might, however, she cannot take the “wrinkles” out of this young man. He remains, perhaps, like us, stoic, obdurate even — bracing himself, taut hands on knees — the sum of his distinct parts.

Scour the internet — that revealer of truths, half-truths, and fantasies — and you will be hard-pressed to find more on the locus of this work and that childhood suffering. Perhaps that is by design, and perhaps it is just as well, for Uribe has said he wants viewers to find “the beauty in the pain” of his paintings and sculptures — not in his biography. And yet that biography is telling.

It could be said, with apologies to Voltaire, that had Uribe not existed, Colombia would’ve had to invent him. It’s a country where voters recently rejected a peace accord in the more than 50-year struggle between the government and rebel forces — the longest war in the history of the Americas. (It’s hinted at in Uribe’s “Bride, General and Rabbi” (circa 2001-2002), in which busts of a cross section of Colombians cluster behind a general, armored in medals, and his bride, whose veil reveals her skeptical, sideward glance.

That half-century conflict echoes a bloody history. The Spanish conquistadores brought to the place they would christen — with equal parts idealisms and portent — New Granada, slavery, smallpox, and a zero-sum game, in which Roman Catholicism would brook no competitor.

The Catholic attitude toward sex, as with those of other religions, is a complex one. The relative openness of Jesus — who nonetheless idealistically equated the sins of thought with those of deed — would combine with the patriarchy of the Hebrew Bible and St. Paul, a seminal figure in Christianity’s foundation, and the reformatory ardor of St. Augustine, the converted playboy who originated the concept of original sin, to create a muddled view of sex and the body that was bound up with torturous (and not so surprisingly titillating) renunciation.

The body, particularly the female body, was considered a vessel of corruption, succumbing as it had to the blandishments of the serpentine Satan that led to humanity’s fall from God’s grace. But humanity would be redeemed by the Son of God made man — a new Adam who would, after the scourging and torture that marked his Passion, die the most excruciating and ignominious of deaths on a cross.

In time, the image of Jesus hanging on a cross would become the central symbol of Western civilization as it journeyed from suffering wraith in the despairing Middle Ages to heroic nude in the Renaissance — a classically inspired period that would also see a revival of the old gods and goddesses as an excuse for indulging in sensual delights. The pietistic Spanish conquerors of Colombia were not immune to the soft-porn glow of these frolicsome, ravished, and ravishing creatures (See the Clark Art Institute’s exhibition “Splendor: Myth and Vision: Nudes From the Prado.”)

It is through the prism then of the beautiful, brutalized body, and sex as art history that the viewer must consider the work of Uribe, who graduated from the University of the Andes in Bogotá and went on to a fine arts masters from the State University of New York at Old Westbury, studying with the influential Uruguayan-born printmaker Luis Camnitzer.

The conventions of formal art and the rich backdrop of Spanish Catholic Colombia are, however, only two of the influences on Uribe’s work. Another is his choice of materials — found objects that marry him to environmental concerns, and his paintings to his sculptures. Indeed, it’s hard to say where one leaves off and the other begins so that his paintings often feature figures who seem to be made out of colored pencils or pieces of them — “pencillism” — juxtaposed with figures of more traditional and painterly strokes.

Uribe’s materials, which have included bullet casings, are not the kinds that are easily recycled into innocuous functionality or traditional beauty. They threaten anguish. “Hooker” (2006) gives us a sculpture of a supremely well-balanced female torso of gold-colored safety pins. You don’t, however, long to caress this torso as you might one of smooth, cool marble. Its spiky beauty is too dangerous.

You have to wonder, then, how the couple in the sculpture “The Embrace” (2009), gets it on: their quill-like bodies melding, so their faces are lost to us. So are their genders. After all, who’s to say that the figure with the black hair, blue shirt, and green pants is male and the blonde one in the pink dress is female? All that is clear is that they are engaged in a thorny intimacy that in other works is jeopardized by the sins of the past — classical, prelapsarian and colonial. Still, they own that intimacy.

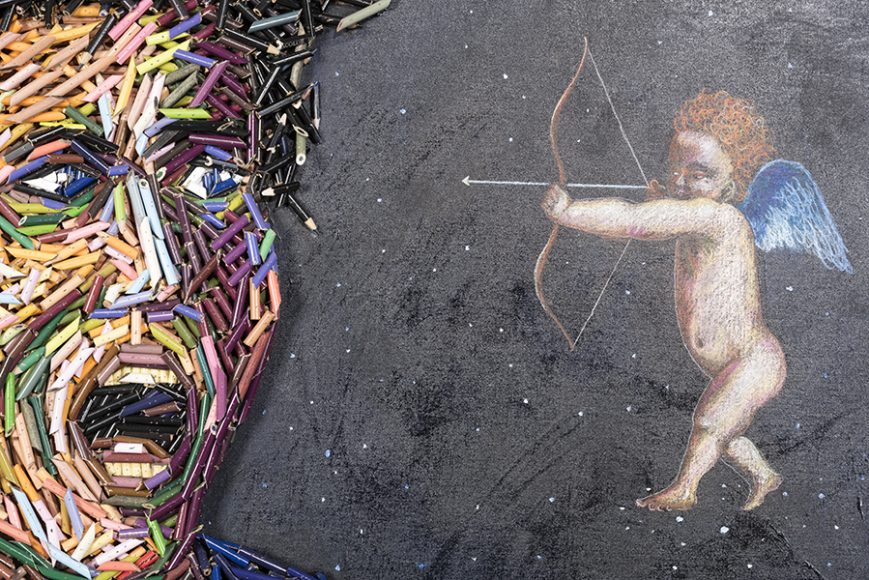

In the painting “The Fear of Cupid” (2014), Aphrodite/Venus’s bad-to-the-bone baby boy takes deadly aim with one of his arrows at a face made of colored pencils cut on an angle like so much penne pasta. That face eyes Cupid, in the guise of a Renaissance cherub, with horror, mouth agape. Clearly not everyone wants to feel love’s sting.

It’s worth dwelling here on Uribe works inspired by another winged creature, the swan, a romantic bird said to mate for life that’s a popular subject in classical mythology, Renaissance art and 19th-century ballet. In the myth “Leda and the Swan,” Zeus, king of the gods, seduces or rapes the Spartan queen, while disguised as the bird, thus fathering the future Helen of Troy (And we know how things turned out for her and the city that would give her its name. Not good).

Uribe’s “Leda and the Swan” paintings dwell on the sexual violence of the myth in contrast to Leonardo’s demure lost canvas on the subject (copied by Cesare da Sesto around 1515) and Michelangelo’s meditative lost treatment, copied by Peter Paul Rubens almost a half century later. One of Uribe’s Ledas lies on a crimson Empire chaise with legs akimbo as swan-y Zeus comes in for a landing, straddling her — wings spread, beak open, one webbed foot resting on her rib cage, lifting a full breast. The other Leda lies partly off-canvas on the grass so that all we see is the rapacious bird as he homes in on its curvy, pink-tinged, headless prey, a webbed foot territorially covering Leda’s vagina. This is hardly like the protective, liberating “wings of the dove” of the Psalms or even of the Henry James novel, which deals with sexual cruelty in a more ceremonious manner.

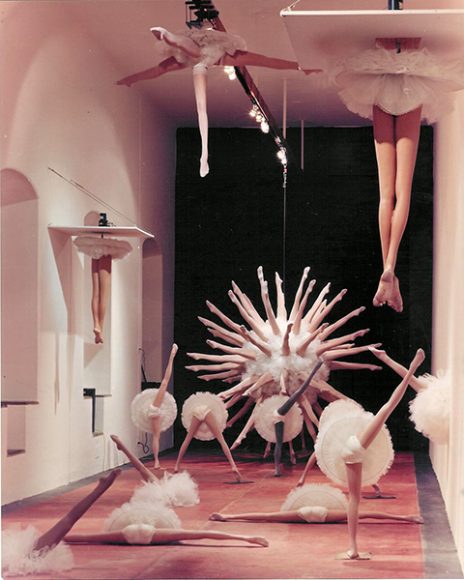

The swan as sexual predator and the bisected female body fuse in Uribe’s installation “Sylphides” (2000), which gives us the splayed lower halves of ballerinas as chandeliers, ceiling fans, and spokes. They’re garbed in the short crinoline tutus of the late-19th century work “Swan Lake,” which presents Woman as both bewitched and bewitching, victim and victimizer. The title of Uribe’s work is something of a misnomer, for “Sylphide” can refer to “Les Sylphides,” a plotless early 20th-century ballet, or “La Sylphide,” a 19th-century ballet about a sprite for whom romantic capture means death. (Those works feature the longer tulle skirt of the 19th-century’s early Romantic period, not the short tutu of “Swan Lake” and Uribe’s work.)

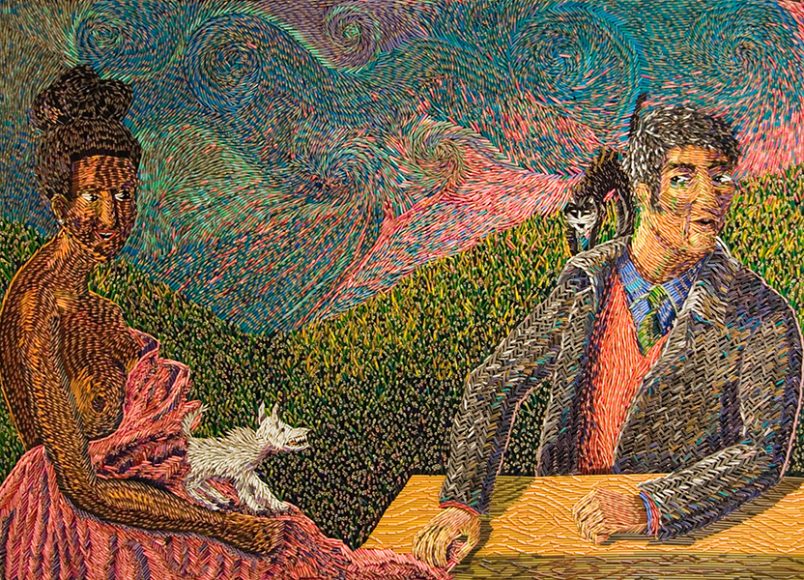

Still, Uribe’s “Sylphides,” “La Sylphide,” as well as “Swan Lake” suggest the same theme — the impossible danger of love with the Other, a not-surprising preoccupation for one who comes from a racially mixed former colony. In “Cats and Dog” (2009), one of Uribe’s pointed “pencillist” paintings, a brown woman eyes a white man who fingers her pink dress, which has been pulled down to reveal ripe breasts in the tradition of Renaissance painting. A small, faithful white dog sits not so subtly on her lap, snarling at the man who turns away, a rearing black-and-white cat on his shoulder. Usually felines are female symbols and dogs, male ones. But dogs are rooted in a person, cats in a place. They like to hunt, suggesting a lover who can’t be trusted.

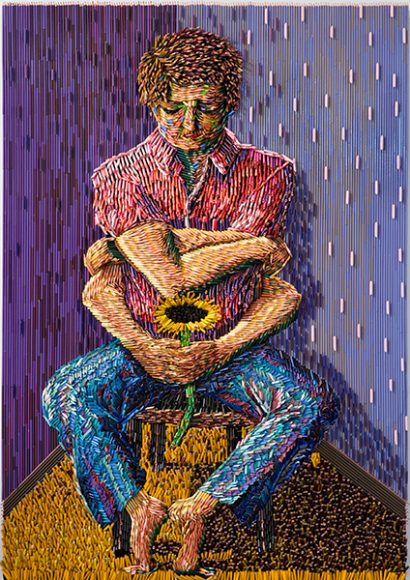

Even Uribe’s masturbatory works — featuring “sex with the one you love,” to quote Woody Allen’s “Annie Hall” — are fraught. In the painting “Single” (2009), a young man sits with his legs splayed, his arms crossed in front to melt into hands reaching from behind his back. Another pair of arms emerges from behind to hold a sunflower where his erect phallus should be. At least it’s a sunflower.

In one of Uribe’s greatest canvases, “Dangerous Love” (2009), a fine, seated male nude leans forward in a lighted room, twisted toward us, lost in thought. The work takes its pose from Anne-Louis Girodet’s “The Funeral of Atala” (1808) and its iconography from Frederic Leighton’s “An Athlete Wrestling with a Python.” Instead of wrapping his arms around the legs of his beloved, as in the “Atala” painting, Uribe’s subject — Adam, as serpent — clings to a phallic snake that rears and hisses. It’s more like sex with the one you love-hate.

Nor does sleep, which Alexander the Great said was the only thing, along with sex, that reminded him of death, offer respite. The older man in the painting “Dream” (2014), lies in bed eyeing an erection that takes the form of a curvy Gibson girl nude, save for a pair of black boots. It’s reminiscent of the images of Uranus, who was castrated by his son Cronos (father of Zeus), and from whose severed parts Aphrodite rose. No wonder some men fear women. They have more than Adam’s rib. They own a man’s sex. They are his sex.

Given the loaded aspect of sex in all its meanings, what’s an artist to do?

Well, he can puzzle it out on canvas, as Uribe does in “The Artist” (2014), in which the title subject puts the finishing touches on a nude’s vagina, evoking Pablo Picasso’s erotic drawings of an artist and his muse. But what is reality and what is art here? With her pink, beige tones, Uribe’s Galatea seems more real than her Pygmalion does, made as he is of pencil-shaped hatch marks. Perhaps there is too much of a divide in this picture plane for a relationship.

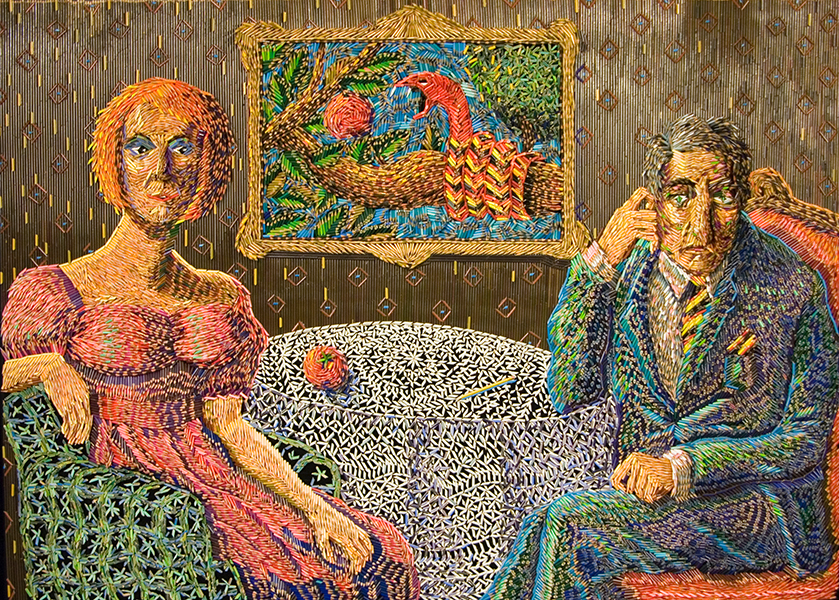

The only hope for sex without fear seems to be framing and containing it. In “The Date” (2009), a couple take the measure of each other warily across a table. On her side sits an apple similar to the one a coiled snake is about to devour in the painting above the table. We might imagine the couple are Adam and Eve, divorced but trying to reconnect long after Eden: Abel is, of course, dead. But they still visit Cain in prison, where he’s working at his online Ph.D in English. (Subject — sibling rivalry in John Cheever’s “Falconer.”) Eve snatches at her pink dress between her legs. Adam nervously fingers a sideburn, shielding his face from her. There is both too much to say and not enough. And so they are like the pair in Simon and Garfunkel’s “The Dangling Conversation,” whose “superficial sighs are the borders of their lives.”

In the sexually explosive works of Federico Uribe, that’s the best you can hope for.