The cycle of family life has an imperfectly perfect symmetry. Witness New York Yankees legend Mariano Rivera.

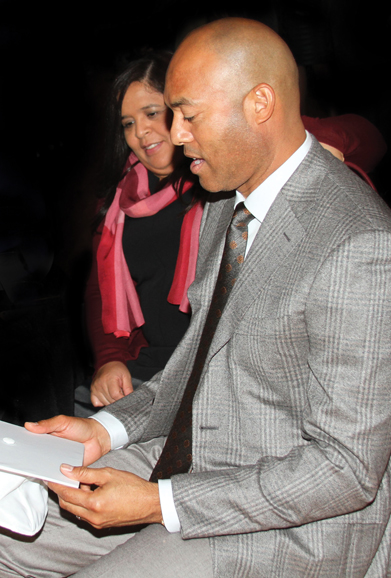

“I didn’t finish school. I went to work,” he told roughly 100 admirers as Latino U College Access honored the Mariano Rivera Foundation during its recent “Visiones: Making College Dreams a Reality” gala at the C.V. Rich Mansion in White Plains.

In the poor Panamanian fishing village of Puerto Caimito — where children fashioned baseball gloves from milk cartons and bats from branches — 16-year-old Mariano worked alongside his father, captain of a commercial boat, catching sardines six days a week. It was long, hard, dangerous work.

But when it came time for another Mariano, the third of that name, to follow in his father’s footsteps and sign with the Bronx Bombers last year, the man who is considered the greatest closer in baseball history — a 13-time All-Star and five-time World Series champion with Major League Baseball records for saves (652) and games finished (952) — said, “No. I wanted him to finish school.”

And so Mariano III graduated from Iona College in New Rochelle — the first Rivera to receive a college degree.

With this, the Latino U audience erupted into applause.

“You may not be cheering in a minute,” Mariano said, a smile wreathing his face as it always did win or lose with the Yanks.

Mariano III has signed a baseball contract, he added — with the Washington Nationals.

Such is the importance of education to Mariano and his foundation — which emphasizes youth programs — that it has partnered with Latino U to award five scholarships. The five students — Lisdy Giron Contreras (Pace University), Daniel Guerra (Iona College), Mariah Jusino (Pace University), Jocelyn Nieto (American University) and Bryam Suqui (Binghamton University) — are the first in their families to go to college. All have faced economic challenges and other struggles to get there but have met them with determination.

“Paying for college was a great concern for my family,” said Lisdy, who presented the award to Mariano and his wife, Clara.

Lisdy credits not only the generosity of the Mariano Rivera Foundation but also God, her parents, who hail from Guatemala, and hard work for getting her to Pace. Now the sky is the limit.

“Someday I hope to work in the criminal justice system and go all the way to the Supreme Court and become another (Associate Justice) Sonia Sotomayor,” Lisdy said.

And why not? As Mariano’s own field of dreams has demonstrated, anything is possible, even for a young, soccer-playing Panamanian fisherman to become the closer for the Olympian Yankees.

Hindsight is always 20/20, particularly when it comes to success. A golden career must’ve always been golden, right? But Mariano met with obstacles, too, after signing with the Yanks in 1990 for a mere $4,700 in today’s money. There were the hurdles of homesickness and a second language. (He advocates English-Spanish bilingualism for sports journalists as well as Latino ballplayers.) Right elbow surgery and a sore shoulder accompanied an uneven record as a starter. But Mariano — one of the “Core Four” along with starter Andy Pettitte, catcher Jorge Posada and shortstop Derek Jeter who debuted with the Yanks in 1995 — developed a stinging cutter (think the movement of a slider with the speed of a fastball) that he used with pinpoint accuracy.

In 1996, Mariano was the setup man behind closer John Wetteland. Their tandem was a key ingredient — along with the avuncular leadership of manager Joe Torre, gutsy pitching from Pettitte and former Mets star David Cone and timely hitting from the likes of Jeter, Posada, (October WAG cover subject) Bernie Williams and catcher (and now manager) Joe Girardi, to name but a few — in an improbable World Series triumph over the vaunted Atlanta Braves, the team’s first since 1978.

But a pitcher bears a disproportionate responsibility for a team’s success or failure. He’s the only one who can get a “W” or “L” after his name. Fans will remember — though they won’t want to — the game-tying home run Mariano gave up to Sandy Alomar Jr. in the American League Division Series the following year that helped end the Bombers’ chances for a Series repeat.

Then came a remarkable run — 1998, when the Yanks fielded what is considered one of the greatest baseball teams ever, with a record 125 wins; 1999, when Yankee Stadium introduced Metallica’s “Enter Sandman” whenever “Mo” came into the game during another championship season, and a new nickname, “Sandman,” was born; 2000, when the Bombers bested their crosstown rivals, the Amazins, in a Subway World Series.

But then came 2001 — the year of 9/11. In Game Seven of the World Series, Mariano blew a save in the bottom of the ninth inning for an Arizona Diamondbacks triumph — his first and only postseason loss. The measure of a man, though, is not only in his accomplishments but in the attitude with which he meets adversity. Mariano has met failure, pressure, team and New York media intrigue and injury with the same affable, organic grace with which he pitched.

He took solace in the 2001 World Series loss sparing the life of teammate Enrique Wilson. (Had the Yanks won, Wilson would’ve stayed in New York for a parade and later boarded the doomed American Airlines Flight 587 to the Dominican Republic that killed all 260 aboard and five people on the ground in Queens.) Mariano has stood by troubled teammate Alex Rodriguez through his steroids scandal and subsequent comeback. He chose to end his career with the close of the 2013 season rather than in 2012 when he suffered a freak knee injury shagging fly balls before a May 3 game against the Kansas City Royals.

“Write it down in big letters,” he told the press: “I’m not going down like this.”

That resilience earned the admiration of Jackie Robinson’s widow, Rachel.

“I’ve always been proud and pleased that Mariano was the one chosen to wear (Jackie’s number, 42), because I think he brought something special to it.”

Mariano has always credited his success and grace to his Pentecostal faith. At the Latino U fundraiser, he talked about another key member of the team — wife Clara, pastor of the Refugio de Esperanza church in New Rochelle that they renovated.

“My wife raised them,” he said of their three boys — Jafet and Jaziel, along with Mariano III. “I was never home. Thank God for her.”

To which many in the audience no doubt silently added, “Thank God for you, too, Mariano.”

Perhaps master of ceremonies Joe Torres, a WABC-TV anchor/reporter, spoke for them when he suggested, “After he speaks, I feel like we should stop. He’s the closer.”

Indeed, for fans of baseball and humanity alike, the name “Mariano Rivera” says it all.