In “The Editor,” Steven Rowley’s new novel, struggling writer James Smale finally gets the break he’s been seeking in 1990s New York. A major publishing house has bought his book, and Smale has been assigned to the editor who pushed for the purchase — Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis. All would seem to be golden except that Smale can’t bring himself to finish his brutally autobiographical tale for fear of exposing the family whose dysfunction he has depicted all too well.

As their working relationship evolves into a friendship, though, Jackie — known as “Mrs. Onassis” about the office — urges him homeward to confront the truth about his past that will enable him to write the book’s authentic ending. That’s when Smale begins to suspect that “Mrs. Onassis” is more than an editor and an icon.

The real Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis (1929-1994) was, of course, both. At Viking Press and then at Doubleday, she would prove to be as passionate about authors — Michael Jackson, Bill Moyers and Martha Graham, among them — as she was about their books.

“She had a deep engagement with literature, history, plays and poetry,” daughter Caroline Kennedy Schlossberg once said of her. “They gave her strength even in the difficult times.”

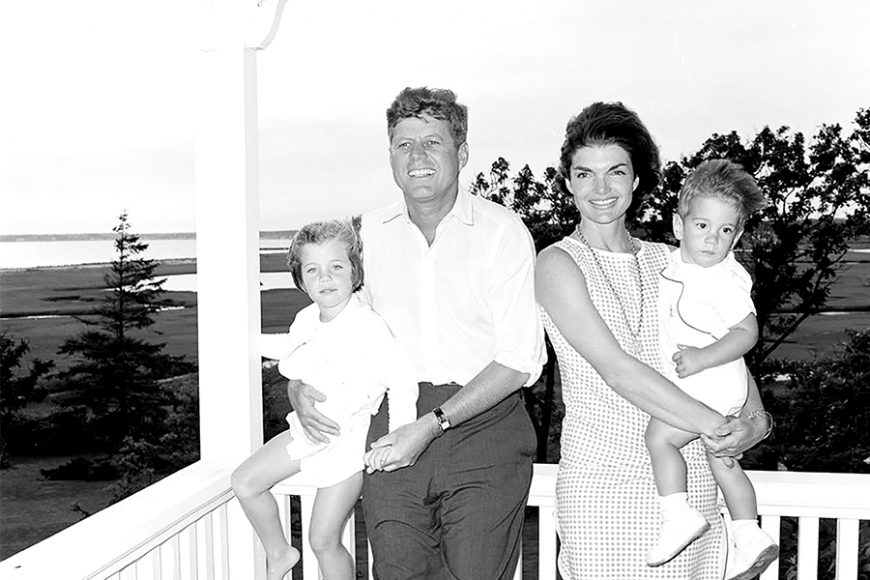

They would inspire a 20-year career in the last act of a life that haunts us still. This month — July 28 — marks the 90th anniversary of Jackie’s birth. This year marks the 25th anniversary of her death, on May 19, 1994. It also marks the 20th anniversary of the death of her son, John F. Kennedy Jr.; his wife, the former Carolyn Bessette, and her sister, Lauren Bessette, in a July 16 plane crash off Martha’s Vineyard.

Anniversaries are times of reflection as we consider lives that have served as rich metaphors through the years, and the lives of the various Kennedys are certainly no exception. People magazine has put out a commemorative issue, “Jackie: A Life in Style,” while Town & Country has a special edition on “Jackie & John F. Kennedy Jr.: A Mother’s Love.”

But Jackie in particular would seem to need no such remembrances, for she’s always with us. Nine decades after her birth and a quarter-century after her death, she remains an enticing, enigmatic avatar of American womanhood.

Part of it was artistic, a strong suit of hers. Tartly witty, she was quoted in her Miss Porter’s School yearbook as saying her ambition was “not to be a housewife.” Later, the lifelong equestrian would remark that the title “first lady” reminded her of a horse. Yet she set a standard of cultural excellence for every aspect of the White House — from its French-flavored cuisine to its classical entertainment to a renovation that restored the “People’s House” to its Federal (turn of the 19th- century) roots.

With a bouffant hairdo created by Kenneth (Battelle) framing her wide bone structure and clothing by Cristóbal Balenciaga, Christian Dior, Hubert de Givenchy and, especially, Oleg Cassini draping her 5-foot, 7-inch frame, Jackie established a look that serves as a muse to the style influencers of today — be it shifts with pearls (Michelle Obama), demure coats and pillbox hats (Catherine, Duchess of Cambridge), cape dresses (Meghan, Duchess of Sussex, Angelina Jolie), black Ts with white jeans (Amal Clooney), dramatic, high-waist belts (Melania Trump) or Grecian goddess gowns (Jennifer Lopez, Gwyneth Paltrow).

Jackie’s style, however, was always more than skin deep. Underpinning it was a singular self-possession, a steely determination to chart her own course on life’s often tempest-tossed seas that has characterized some of America’s greatest icons, including Muhammad Ali and Marlon Brando. It’s a quality we can’t get enough of, even as it holds us at arm’s length.

In Jackie, it was probably born of being an introvert cast into the public arena whose genteel circumstances were not as plush as they seemed. Her adored father, John Vernou Bouvier III, nicknamed “Black Jack” for the striking dark looks his older daughter would inherit, suffered from alcoholism, adultery and the vagaries of Wall Street. Her controlling mother, the former Janet Lee, set the standard for her daughters to make wealthy matches by divorcing Black Jack and marrying Standard Oil heir Hugh D. Auchincloss.

Was Jackie’s self-containment a defense mechanism against richer step- and half-relations? Or was it just her way? Look at her as she strides across the grounds of the Southampton Riding and Hunt Club in a now classic photograph, her 5-year-old self leading her pony, Buddy, her mouth turned down at the edges as she peers hard at the photographer. It’s a look that says, “I am complete in myself.”

I experienced that impenetrable integrity covering the 1981 premiere of Twyla Tharp’s “The Catherine Wheel” in Manhattan. As I went to exit the Winter Garden Theatre, a man rudely pushed me out of the way. I soon saw why, for there was Jackie, radiant in shimmering couture, jewels and paparazzi flashbulbs. It was like a religious apparition or the deus ex machina at the end of a Greek tragedy. As the crowd parted, she swanned by — the patented middle-distance gaze and vague smile firmly in place on her masklike face — part goddess, part ghost.

Jackie’s Jackie-ness — her aura of aplomb and aloofness, her love of history and theater — would come together in the 1963 assassination of her first husband, President John F. Kennedy. As her family — particularly sister Lee Radziwill — held her together, she held the nation in thrall as a study of unbelievable poise in the face of overwhelming grief.

In the year that followed, she returned to the place she knew first — New York, the place of reinvention — where she reimagined herself. She had already embodied so many stages of womanhood — child, student (Vassar College, George Washington University), working girl (the Washington Times-Herald’s “Inquiring Camera Girl”) and, especially wife and mother. To these, she would add divorcée, after a brief marriage to shipping magnate Aristotle Onassis, career woman and “Grand Jackie” (to Caroline’s three children).

What would she be like at 90? Still editing? Writing a memoir to be sealed for 100 years? Great-grand Jackie?

You can bet she’d have none of our 24/7 digital celebrity culture but would instead be peering at us now as she did then, sphinx-like, daring the world to intrude, still guarding her secrets.

Jackie never divorced. Aristotle Onassis died on March 15, 1975, leaving Jackie a widow for a second time.