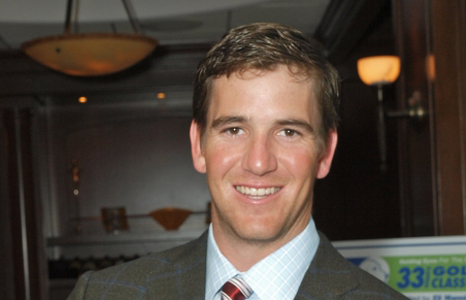

If you were going to cast a classic movie star to play New York Giants’ quarterback Eli Manning, whom would you pick?

Possibly a young Duke Wayne. Or maybe Jimmy Stewart. More likely, you’d select the Gary Cooper of either his “Meet John Doe” or “The Pride of the Yankees” periods – all “aw, shucks” charm, solid work ethic and bedrock decency that belie a certain canniness.

Here was Eli navigating a minefield of a question about his “rivalry” with Denver Broncos’ quarterback and bro Peyton Manning as he hosted the annual Guiding Eyes for the Blind Golf Classic this past June at the Mount Kisco Country Club:

Q. Are you trying to be the No. 1 quarterback in your family?

A. “No, I don’t try to be the No. 1 quarterback in the family. I’m trying to be the No. 1 quarterback for the New York Giants.”

The answer was modestly submitted. Eli is a shy guy. But when we offered a hand to thank him for taking time to consider the press’ questions, he stopped to shake it firmly and meet our gaze with “You’re welcome.” And right then we got the sense that his self-contained temperament is trumped by a desire to reach out and serve others.

“He’s a true gentleman,” says Michelle Brier, director of marketing and communications for Guiding Eyes for the Blind. “He has this innate kindness. He’s never self-promoting.”

Yet he’s more than willing to raise his voice for a good cause; like Guiding Eyes. Since it began in 1954, the Yorktown Heights nonprofit has helped more than 7,000 visually impaired and autistic individuals by providing them with free guide dogs that the organization trains. Guiding Eyes’ golf classic, founded in 1977 by PGA legend Ken Venturi, has raised more than $8 million with an annual two-day event at Mount Kisco Country Club and Fairview Country Club in Greenwich. Eli has helped raise almost half of those funds since he got involved in the event seven years ago when Patrick Browne Jr., a perennial United States Blind Golf Association champ and Manning family friend, asked him to step in for the retired Venturi (who died this past May).

When Eli first started, he wasn’t much of a dog person, Brier says.

“He had never had a pet dog and he didn’t want to hold the puppies. Now he loves holding them and snuggling up with them.”

And he and wife Abby, who live in New Jersey, are the proud parents not only of two little girls, but of a Cavalier King Charles Spaniel named Chester.

Brier said Eli is there throughout the two-day event – golfing, meeting the press, greeting donors at the culminating dinner and bidding on the auction items. He talks up Guiding Eyes wherever he goes, she says.

But perhaps the depth of Eli’s commitment to the organization can be measured in his willingness to stand on the putting green of the Mount Kisco Country Club on a rainy, bone-gnawing day more characteristic of November than June to try to sink a putt blindfolded to demonstrate what it’s like for a visually impaired golfer. And he damn near sank the thing, a tribute to the true athlete’s sense of his body in a space, even when deprived of his sight.

Eli, however, knows what’s really awe-inspiring here.

“I’ve seen firsthand how people have been helped because of these guide dogs. There are a lot of amazing stories,” he says, referring, for example, to how the Heeling Autism program gives autistic children a certain independence and their parents peace of mind. “It’s been a pleasure to be a part of this.”

A quarterback, of course, doesn’t use his voice for just charitable purposes. He’s calling plays and exhorting players in the huddle and in the locker room. Though we tend to think of singers, actors and orators when we think of voices, a quarterback has to have a pretty good set of pipes, too, to be heard over the crowd, the so-called “12th man” in football. How does Eli make himself heard?

“The team practices with loud crowd noise playing over the speaker so that players can get used to projecting their voices. Often practices are louder than games.”

With the Giants off to a terrible start, there are critics who wish Eli would make his voice heard off the field more as well.

“He does get up to speak in the locker room as team captain,” says sportswriter Ernie Palladino, who has covered the Giants for 24 seasons and is the author of the new “If These Walls Could Talk – New York Giants” (Triumph Books). “But he’s not a yeller. He’s not going to call people out or turn over furniture. He leads by example.”

Yet there’s no denying his on-the-field performance, has been hushed so far this season by too many interceptions, sacks and turnovers, in which the offense and defense must also share.

We’ve been there before, though, haven’t we? From the moment Eli bowed with the Giants in 2004 – after being drafted by the-then hapless San Diego Chargers and adamantly refusing to play for them – it’s been the same song. Not a take-charge guy. Not an elite quarterback. Not Peyton.

Ah, yes, Peyton: No Eli profile is complete without a discussion of the rivalry – no doubt rooted in reality but also heavily media-manufactured – between the commanding, glamorous older brother and the retiring but resilient baby brother. They were born and raised in New Orleans, the second and third sons of American football royalty – New Orleans Saints’ quarterback Archie Manning and his soft-spoken wife, Olivia. The oldest son, Cooper, was a talented high school wide receiver sidelined by spinal stenosis, whose condition, according to the new documentary “The Book of Manning” had a profound effect on shaping Peyton’s career.

The more rough-and-tumble Cooper and Peyton were Archie’s boys; the laidback Eli, nicknamed “Easy E,” more his mother’s son, who enjoyed dining out with her and accompanying her when she went antiquing. She in turn helped him make his voice heard.

Stories about the Mannings of New Orleans are legendary and character-revealing – how Peyton would use his knees to pin Eli by the arms and make him recite the names of all the NFL teams; how Cooper and Peyton once watched Eli tumble down a flight of stairs. The 3-year-old picked himself up, dusted himself off and ran off to play.

That incident was perhaps a harbinger. On Dec. 29, 2007, an up-and-down Giants team faced off against an undefeated New England Patriots team. With nothing to gain – the Giants had already secured a playoff spot – and everything to lose by risking injury to their starters, Eli and the Giants nonetheless decided to go all in to attempt to stop the Patriots’ perfect regular season. The Giants lost 38-35 but they demonstrated that they could hang with the best and echoed something that Teddy Roosevelt once said:

“It is not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly; who errs, who comes short again and again, because there is no effort without error and shortcoming; but who does actually strive to do the deeds; who knows great enthusiasms, the great devotions; who spends himself in a worthy cause; who at the best knows in the end the triumph of high achievement, and who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who neither know victory nor defeat.”

Several weeks later, the two teams met in Super Bowl XLII. As any highlight-reel buff will tell you, Eli threw a crucial pass in the last 2½ minutes that David Tyree nailed on his helmet and then another to Plaxico Burress for a touchdown. And the Patriots’ perfect season was gone. The Giants won, 17-14, and Eli was Super Bowl MVP. In the 2011-12 season, it was déjà vu all over again.

Now Super Bowl XLVIII is coming to New York and New Jersey, and Eli would love to be a part of that.

“Every year, you want to play in the Super Bowl. But to be the first team to play in your home city, that would be neat.”

The odds aren’t good, but as Palladino said, “He’s been a Captain Comeback, and he does that through his quiet voice.”

And by being the man in the arena, who takes his best shot, even with a blindfold on.

We wouldn’t bet against him.

Eli’s and Peyton’s greatest hits

Sure, sure Peyton is 3 and 0 against Eli on the field, but what about where it counts, in using their voices as rappers, pitchmen and hosts of NBC’s “Saturday Night Live”?

Peyton has done some “Priceless” Master Card commercials. Eli has scored with Toyota and Dunkin’ Donuts. The two teamed as football-wielding cops and ’80s rappers for DirecTV.

Peyton was at the top of his game hosting “SNL,” particularly in a fake public service announcement with a group of kids, in which he plunked one with a football, then banished him in disgust to a Porta-Potty before teaching the gang how to break into a car. But Eli countered in his “SNL” gig with a fake PSA of his own endorsing Little Brothers, an organization that turns the tables on big brothers like you know who.

“Maybe now you’ll learn to treat your younger brother with some respect, Peyton,” Eli shouted as he locked Andy Samberg in a car trunk.

“My name’s not Peyton,” Samberg screamed.

“Whatever,” Eli said as he slammed the hood. You think there was more than a touch of Method Acting there?

As for who was more, um, Brando-esque, Eli told WAG, “Neither of us should leave his day job.”