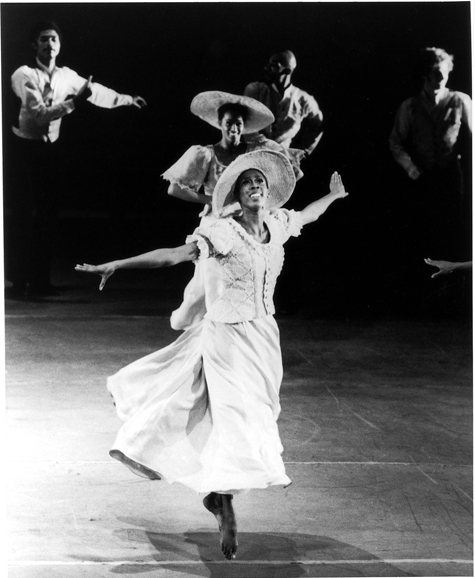

Tall and regal, Judith Jamison strides onto the stage of The Regina A. Quick Center for the Arts at Fairfield University with the élan of the international dance star she was and remains.

“Hello, I’m Ellen DeGeneres,” she says to laughter and cheers from the audience. “And I’m not giving anything away.”

But then, she has already given so much. Joining the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater in 1965, she quickly became Ailey’s muse, creating some of his most indelible roles, including the virtuosic solo “Cry,” which leaves both the performer’s and the audience’s souls laid bare; and one half of a complementary pair in the delightful “Pas de Duke,” which Ailey made for her and Mikhail Baryshnikov. During the following decades, she appeared as a guest artist around the world, headlined the Broadway hit “Sophisticated Ladies” and founded her own troupe, The Jamison Project.

When she returned to the Ailey company in 1989, it was to become artistic director at his request and take the company to the next plateau that would include two historic South African engagements and a 50th anniversary, 50-city tour.

Taking part in Fairfield University’s signature lecture series, “Open Visions Forum,” Jamison credits the people she’s surrounded herself with over the years for their guidance, which has led her to find such remarkable success. Born in 1943, she grew up in Philadelphia — “not the City of Brotherly Love at that time,” she says. During her youth, she saw the birth of the Civil Rights Movement. “There were countless people not on the front lines who were dealing with things that required strength,” she remembers. “That was my parents.”

Even in the face of segregation, Jamison felt protected, loved and safe, due also to her grandparents, who lived right next door.

“I was protected from degradation. My parents knew where to lead us. When we (she and her brother) saw derogatory things, they’d acknowledge that this wasn’t who we really were.”

Like many successful couples, her parents were complements. Her father, “a Southern gentleman,” didn’t even blink when her mother raised her voice to him. But not much later, Jamison and her brother would peek around the corner into the living room to find their parents dancing together cheek-to-cheek, as if the fight never happened.

“Their resourcefulness and can-do spirit really boosted what my brother and I learned about how to be hard-working.”

Jamison’s mother was fond of quoting Shakespeare to her children. Jamison’s father was a sheet-metal mechanic and carpenter. “He made our dining room and kitchen cabinets. He made a stainless steel grill for our backyard. I’m smiling, because it was a wonderful time in my life.”

A man of many talents, Jamison’s father could also play classical piano and sing opera. “He taught me how to play the piano,” Jamison says, recalling how his rough, calloused fingers would nonetheless move delicately over the keys, creating a sound so soft and melodic, she couldn’t help but notice the paradox in it, even as a child.

“I danced the way I danced because of all those opposites and what was in the middle — the love my family had for each other.”

She was 6 years old when she performed for the first time. At that age, she had no real idea if she wanted to be a dancer, but she remembers that first performance. “I was scared to death. I remember being blinded up on stage, the curtain going up, going down and people applauding. That did it. I loved dance.” From then on, she did all she could to keep dancing, learning as many styles as she could, including ballet, tap and modern. All of her hard work, drive and passion paid off in 1964 when choreographer Agnes de Mille (“Rodeo,” “Oklahoma!”) invited her to join American Ballet Theatre for a performance.

“At the time, the closest they could get to brown at the theater was Latino. So that was truly marvelous.” Even more marvelous was the way she made it to Alvin Ailey, immediately after an unsuccessful audition with another choreographer — a blessing in disguise.

“The relationship wasn’t so much about what he said to me,” Jamison remembers. “It was very spiritual. He would dance and we’d follow him. When I learned ‘Cry,’ I was learning the steps. I read in the program the next day what the dance was about” — a 16-minute piece dedicated to his mother and black women everywhere.

“Mr. Ailey was a person dedicated not only to his craft, but to each person he worked with, as well as the community that he felt the theater served. He instilled this love of the world in his dancers as well. Mr. Ailey was only interested in who you were as a person. He wanted us to go outside of dance and meet other people in different disciplines so that we’d have something to say to the world about what it is to be human.”

It was that kind of leadership that prepared Jamison to take over the company when Ailey died in 1989. For the next 21 years, she continued his legacy, bringing the troupe out of debt and finding new success.

“Alvin Ailey has been integrated since its inception,” Jamison, now artistic director emerita, is proud to say. “Mr. Ailey welcomed everyone. That’s a part of my experience. That’s a part of my learning how to be artistic director.” It was a lesson she’d been learning since she first stepped onstage with his company, facing audiences that sometimes saw the color of her skin first.

“It’s something to fight, but it’s something to ignore. When I’m onstage, I’m not thinking about not being able to get a cab after the show. I’m thinking, ‘I’m going to tear it up.’”